Sept. 2, 1838

Sept. 2, 1838. A black coachman, a freeman named Isaac Rolls, stashes a duffel bag in the rear of a train at the Baltimore station. Under a cloak of impending darkness, a twenty-year-old in a black sailor’s uniform waits in the weeds. He looks down and pulls a weed, pinching off a piece of the pale root…

“De white man, dey won’t harm you if you carry dis root.”

Sept. 2, 1838. A black coachman, a freeman named Isaac Rolls, stashes a duffel bag in the rear of a train at the Baltimore station. Under a cloak of impending darkness, a twenty-year-old in a black sailor’s uniform waits in the weeds. He looks down and pulls a weed, pinching off a piece of the pale root. An old slave, Sandy Jenkins, known as “the root man” because of his rudimentary knowledge of botany, once told him “de white man, dey won’t harm you if you carry dis root.” Wive’s tale or not, Frederick Bailey slips the root into his pocket. He hears the conductor. “Last call for Havre de Grace, Wilmington and Philadelphia. All aboard!” The young man watches the conductor pick up the step and pack it inside the door of the train, before closing the door.

Puffs of steam and coal soot belch from the smokestack. The brakes release, and the train lurches forward, steel on steel, as the engine’s piston arms strain to pull the weight of a half-dozen cars. It picks up speed, and as it clears the station, young Bailey emerges from seclusion, running to catch up to the train’s caboose. The back rail of the moving train eludes his grasp, but his legs are fast, and with a second effort, his black hand grasps the rail and he pulls himself aboard. He picks up the duffel bag, negotiates his way on the moving train to the middle of the car reserved for colored passengers, places the bag on an overhead rack and sits close to the window.

The Maryland countryside passes outside. Occasional squares of candlelight and gaslights in houses dot the landscape. A man and woman several rows ahead engage in flirtatious conversation, and to the rear of the car, five men throw kings and queens and coins on a piece of luggage in the aisle, shouting and piercing the rhythm of the train as they engage in a raucous card game.

The conductor makes his rounds, collecting tickets and fares. In this car, the rules state he must also assert whether the clientele are free to travel. Frederick’s heart beats fast, like a rabbit being chased by wolves. He mops beads of sweat from his brow with the red cravat that is part of his ruse. The conductor stops when he gets to Frederick.

“Have you got your free papers?”

Frederick looks at him directly.

“No, sir. I don’t have any papers.” The conductor looks at the muscular young man in uniform, disappointed in his apparent attempt to flout the law. Frederick continues, “But I have this paper with an eagle on it that will carry me around the world.” He hands the Merchant Marine conscription paper to the conductor. If the railman took the time to inspect the paper, he would have seen that the paper belonged to a Mr. Stanley Johnson who was much shorter than Bailey and did not come close to matching his description. But the railman is distracted suddenly as a fight breaks out among the card players in the back of the car. He hands the paper back to Frederick and hurries to break up the melee.

Frederick says a prayer of thanks to a God who, to this point, has seemed to have had little interest in Frederick Bailey.

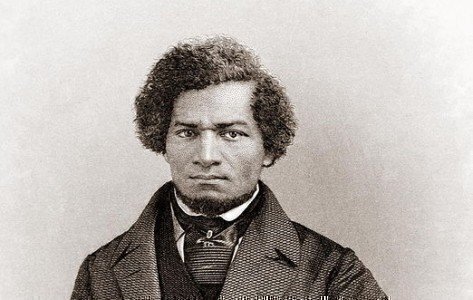

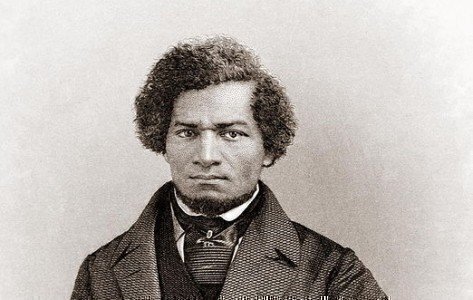

So began Frederick Douglass’ escape from slavery. After more harrowing events along the way, he arrived in New York City as a fugitive slave. He made choices, many placing him in the crosshairs of danger as a human being seeking equity in a white man’s world that was not conducive to men and women of color.

That was 185 years ago today, and the train of harmony and equal justice still hasn’t pulled into the station. It’s all the more reason that my award-winning script telling Douglass’ journey from self-educated slave to the father of American civil rights needs to be produced as a feature film or streaming series. It’s been a 15-year odyssey for me so far, but I haven’t given up.